Coordination in the distributed systems

Some user requests might be handled by a group of services in your system. For example, you take an order, process payment and ship that order. And these steps might be located in different parts of your application because each service is responsible for a small piece of the domain. Of course, these services must process the order in a certain sequence. Let’s take a look at how to organize this interservice communication.

There are two main patterns: choreography and orchestration.

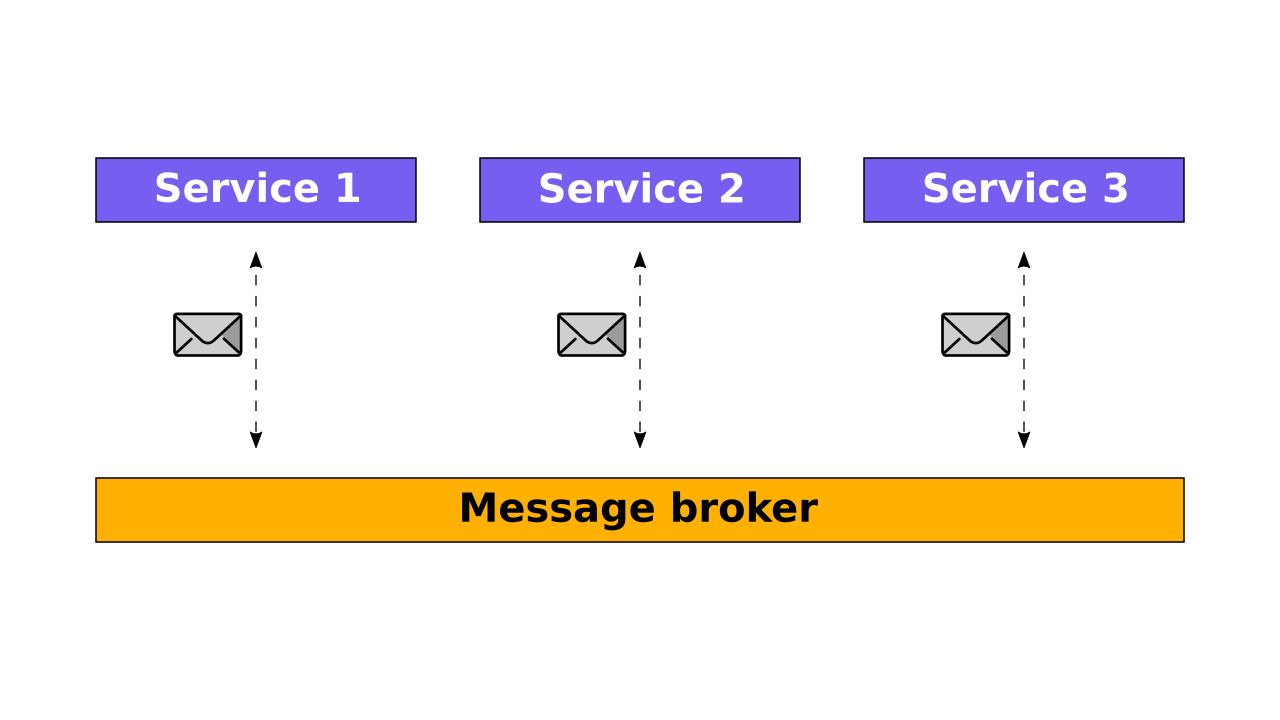

Choreography

In this pattern, each service subscribes to events from the others. When an event comes, the service executes its action and produces a new event. Eventually, you have a chain of the services which handles the request sequentially.

Choreography reduces coupling in your system because the services don’t know anything about each other. All they know is the events to come to them.

Some services may not handle events but enrich them. These services add some useful information from their databases to the message and resend it. Thus, the next service in the chain can use more data. This approach is similar to the pattern Pipes an Filters.

The downside of the Choreography is that it’s possible to describe only elementary processes with the subscribing to the events. If you have many steps with conditions, cycles and parallel steps, Choreography isn’t for you.

Another weakness is a large number of services. It’s troublesome to maintain systems with many events and subscriptions. You don’t exactly know which services will be triggered by certain events, and a vast amount of traffic is passed through the message bus.

Also, it’s challenging to recover from failure. If a service falls and doesn’t send any event, your process will break down, and other services won’t know about it.

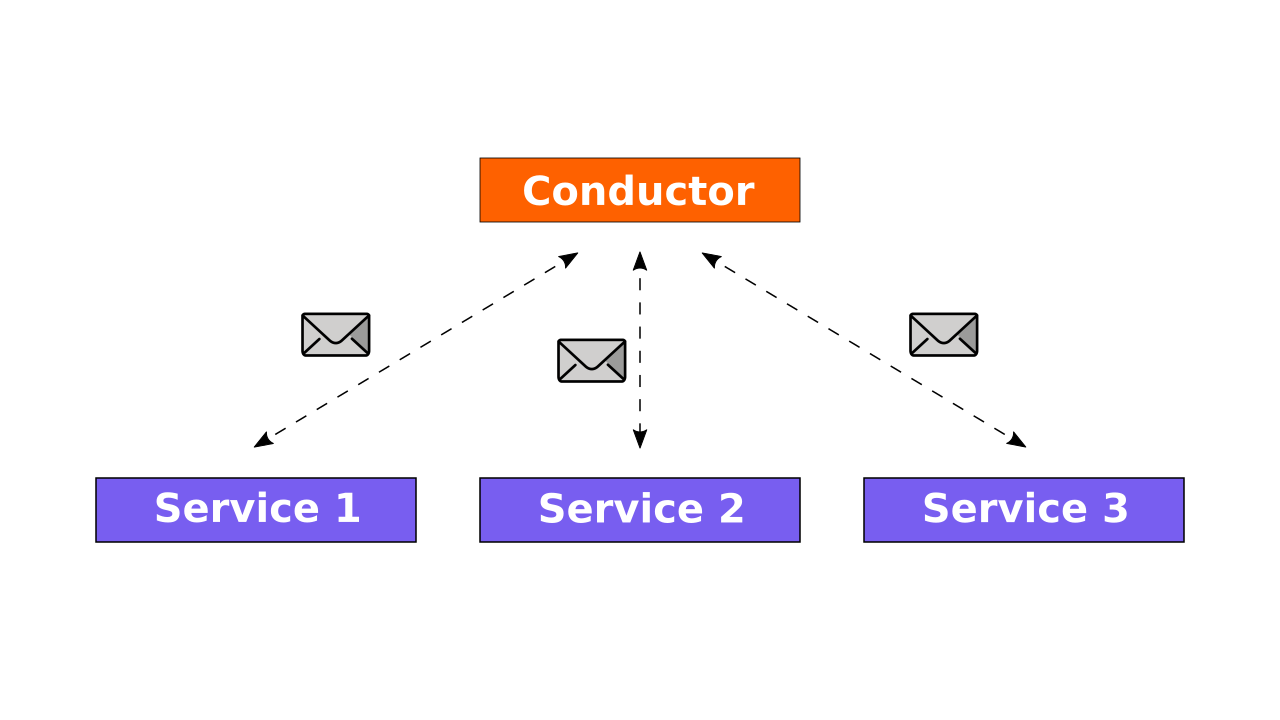

Orchestration

In this pattern, you have one central service called a conductor. It knows the workflow and sends commands to the other services. In its turn, the service executes the command and responds to the conductor.

With orchestration, you can create complex and tricky workflows by describing them in your conductor. Also, the conductor deals with all failures in the system. It waits for the services responds, retries the requests, notifies system administrators.

The main drawback is that the conductor is a single point of failure. If it falls, your system won’t handle users requests. Furthermore, there is a high coupling between the conductor and services. In the distributed systems, you should avoid any coupling between components. Eventually, most of the domain logic ends up in this central service, and it becomes responsible for everything.

Saga

Sometimes you need to accomplish all steps in your pipeline or undo everything if one of the steps failed. If you have one database, it’s simple to achieve by using a database transaction. But in the distributed systems each service has its own database, and this straightforward solution doesn’t work.

Another way is a distributed transaction or two-phase commit (2PC). However, this approach doesn’t work either because many modern databases or queues don’t support this protocol, and this pattern reduces system availability. In distributed systems, you have to choose between availability and consistency (see CAP theorem).

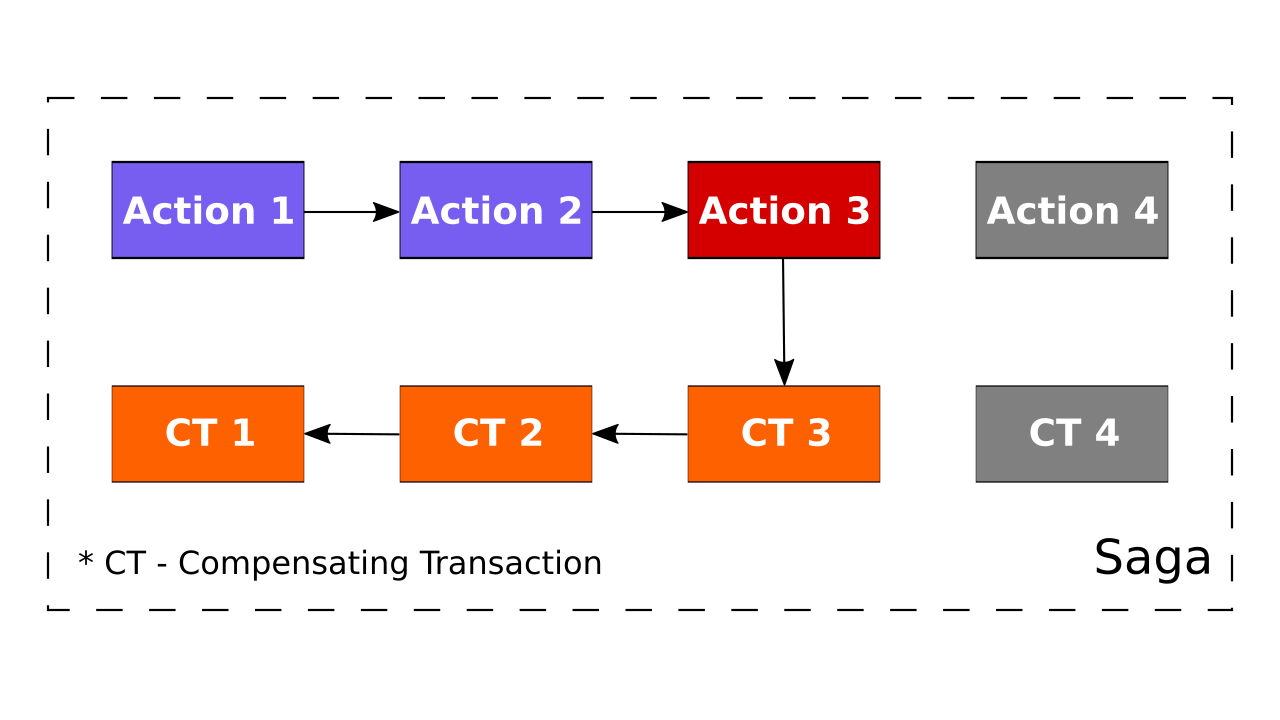

Fortunately, there is a pattern called Saga. It was initially formulated by Hector Garcaa-Molrna and Kenneth Salem in the article in 1987.

In short, the saga is a sequence of steps, and all steps have compensating transactions. If something breaks down, this transaction undoes the effect of the corresponding action. So, in the end, all steps will be accomplished or compensated.

Also, each action affects only one service. Therefore, within a step, we can use a local transaction. In summary, we might say, that saga is a sequence of local transactions with appropriate compensating transactions.

In some situations, it’s impossible to revert some actions. For example, sending an email, you can’t return it back. You should send a new email with excuses. So, compensating transactions might be tricky.

One more thing to consider is that sagas are eventually consistent. Changes in different services will be available at different times. So, it’s a good idea to mark some objects as pending during the saga. It will prevent other processes from reading or modifying these objects.

This pattern is often built on the choreography and orchestration patterns. After all, you need to establish an interaction between services. In the orchestration model, the orchestrator executes the saga and compensates actions if required. Choreography one is not so obvious, because with elementary publish/subscribe mechanism you can’t guarantee, that all steps will be undone.

Routing Slip

The solution here is to attach the list of steps and compensations to the message — this pattern called Routing Slip. Each service performs its action and sends to the next one from the list. Same with compensation. Thus, you use the network as a database. With this pattern, you can check if all steps complete or compensated.

Conclusion

Today, I’ve shown you how to coordinate services in the distributed system. Mainly, we have two options: choreography and orchestration. Also, we’ve considered an analogue of transaction in the distributed world - pattern Saga. In the next posts, I will demonstrate to you some examples of these pattern’s implementation.

References

- Choreography pattern

- Saga distributed transactions pattern

- Compensating Transaction pattern

- Starbucks Does Not Use Two-Phase Commit

- Process Manager

- Routing Slip

Image: Photo by Daria Nepriakhina on Unsplash

Comments